Parenteral nutrition

Information for patients and caregivers

According to an estimate by the G-BA* from 2016, around four in one million people receive parenteral nutrition.[1] Thus, it can be assumed that many people don’t know anything about it. If you are not personally affected or work as a professional in this field, you might have never heard the term before. When patients receive their first diagnosis, it is therefore often a challenge even just to get a basic understanding: What is parenteral nutrition, exactly? How does it work in everyday life? What kind of risks come with this therapy and how can they be avoided? This article offers an overview of the most important questions and answers to help patients and their caregivers get started.

*G-BA stands for "Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss" (Joint Federal Committee). This is the highest decision-making body of the joint self-administration in the German healthcare system.

Overview

- Definition: What is PN?

- Indication: Who needs PN?

- Composition: What does PN consist of?

- Access: How does PN enter the body?

- Application: Where and by whom is PN administered?

- Safety: What needs to be considered?

- Prevention: How can complications be avoided?

- Cost coverage: Who pays for PN?

- References

The term "parenteral" comes from ancient Greek and combines the terms "para" ("past") and "enteron" ("intestine"). Literally, it means "past the intestines". The name sums up perfectly what parenteral nutrition is: artificial or clinical nutrition that completely bypasses the gastrointestinal tract. Nutrients are not taken in through the mouth as normal food, but in liquid form through a central venous access (i.e. a catheter). The correct medical definition thus reads "direct infusion of small-molecule nutrient solutions (so-called emulsions) into the bloodstream". Hence the term “intravenous nutrition” is also used in this context.

Parenteral vs. enteral nutrition

The intestine has many important functions for our body. Apart from the absorption of food, it plays a crucial role in regulating our immune system. In medical treatments, the natural activities of the intestine should always be maintained or restored as far as possible. Parenteral nutrition only serves as a last resort if both oral and enteral nutrition intake is no longer an option. “Enteral” means that patients receive nutrients through a tube or a stoma. This bypasses the oropharyngeal area, but the food is still digested via the gastrointestinal tract. In a broader sense, enteral nutrition also refers to the clinical administration of liquid nutrition.

Parenteral nutrition can be differentiated according to various criteria:

- Is it carried out exclusively or in addition to other forms of nutrition?

- What type of catheter is used?

- Is it carried out at home or in the intensive care unit?

| Parenteral nutrition | Enteral nutrition | |

| Administration | venous access | via tube (e.g. percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube, PEG) or orally |

| Composition | highly concentrated special solution with all essential nutrients | tube feeding and liquid nutrition with all or selected nutrients |

| Food intake | directly into the bloodstream | via the gastrointestinal tract |

Total vs. supplemental parenteral nutrition

We can distinguish between two types of intravenous nutrition – depending on the patient’s needs.

- Supplemental parenteral nutrition (SPN) serves as an additional measure in combination with oral or enteral nutrition. It comes into play when patients can take in food through the mouth or a tube, but do not receive all the necessary nutrients in this way. SPE can then compensate for this deficiency.

- Total parenteral nutrition (TPN), on the other hand, covers all nutrient requirements intravenously. This becomes necessary if the gastrointestinal tract can no longer function due to illness or injury.

Many patients with TPE in fact continue to eat "normally". Contrary to healthy people though, normal food is not utilized by the body, but simply passes through the intestines and is then excreted again. Nevertheless, regular, orally administered meals remain important for several reasons: On the one hand, eating simply means enjoyment and quality of life, especially as the stomach continues to send hunger signals. On the other, the gastrointestinal tract (and all associated processes in the body) should be kept as active as possible.

Parenteral nutrition is used when the nutritional requirements cannot be (sufficiently) covered by normal food or a feeding tube. This might have a variety of reasons:

- short bowel syndrome (small intestine partially or completely absent)

- chronic inflammation in the intestine (e.g. Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis)

- cancer diseases

- inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis)

- disturbance of food utilization (malabsorption)

- metabolic disorders (e.g. hypermetabolism in sepsis)

- extreme persistent diarrhea

- massive underweight (cachexia)

- coma

- severe injuries (e.g. burns)

- aids

- gastrointestinal bleeding and perforations

- care of premature or sick newborns

Parenteral nutrition in oncology

Cancer (and associated treatment) can affect a patient's nutrient supply in many ways, regardless of whether the gastrointestinal tract is directly affected by tumours. The growth of cancer cells often leads to a metabolic disorder (so-called tumour cachexia), which causes patients to lose more and more weight. Aggressive radiotherapy and chemotherapy can also deplete the body severely. If the increasing undersupply cannot be compensated for by oral or enteral nutrition alone, patients might rely on supplemental parenteral nutrition. SPE can also be used in a palliative context to prolong the lifespan and improve the quality of life. Whether and for how long artificial nutrition is helpful in such cases must be decided on an individual basis in close consultation with the patient and their caregivers.

Parenteral nutrition due to chronic intestinal failure

A common trigger for parenteral nutrition is short bowel syndrome. The diagnosis itself is very rare: According to estimates in Germany, it affects only one in 100,000 people. Of these, around 30 % receive parenteral nutrition.[1]

Short bowel syndrome occurs when the length of the functional small intestine is reduced by at least 50 %. There are many possible causes:

- arterial or venous vascular occlusions

- volvulus (twisting of the bowel, especially in children and adolescents)

- traumas

- tumour diseases

- chronic inflammatory bowel diseases

- severe inflammation or scarring

The symptoms of short bowel syndrome vary, depending on which sections of the intestine are affected. The following symptoms may typically occur in the early stages:

- massive diarrhea with sometimes high fluid and electrolyte losses

- weight loss

- lactose intolerance

- kidney stones and gallstones

- osteoporosis

Attempts to counteract such symptoms by drinking more have the exact opposite effect: Increased fluid intake accelerates the passage through the intestine, which in turn leads to increased diarrhea. Ultimately, parenteral nutrition presents the only way to compensate for the loss of fluids and nutrients when a patient suffers from short bowel syndrome. Under certain circumstances, the remaining small intestine might regenerate during the course of treatment. In the best-case scenario, parenteral nutrition can then be reduced or even discontinued completely. If only a small part of the remaining small intestine remains (less than 50 cm), the patient suffers from chronic intestinal failure. Those affected usually remain dependent on parenteral nutrition for the rest of their lives.

Contraindication: When is parenteral nutrition not possible?

Feeding through a venous access is a very invasive procedure that carries many risks. Therefore, this method cannot be applied in the following cases:

- up to 24 hours after a surgical procedure or trauma

- severe acidosis (hyperacidity of the body)

- state of shock

- hypoxia (lack of oxygen supply)

Parenteral nutrition also should not be used if enteral (via tube) and/or liquid nutrition is feasible – or if the remaining life expectancy is less than one month. Generally, patients or their legal representatives must always give their consent for the prescription of parenteral nutrition. This applies to palliative care as well as to all other medical fields.

A parenterally administered nutrient solution must fulfill three essential functions:

- stabilise the organism

- strengthen the immune system

- increase or maintain body weight at a healthy level

For that purpose, most patients use three-chamber or multi-chamber bags. As the name suggests, these bags are divided into individual components (chambers). This means that the nutrient solutions remain stable for longer in the sealed bag. All components are then mixed together shortly before administration. They provide a complete supply of all essential macro- and micronutrients:

- glucose solutions

- amino acids

- fat emulsions

- electrolyte solutions (sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, phosphate)

- vitamins and trace elements

However, not all vitamins and minerals can be administered in sufficient quantities through parenteral nutrition. Patients usually require a separate supply of certain micronutrients, especially vitamin D and iron. Medication must never be mixed into the nutrient solution.

The majority of patients can rely on industrially produced multi-chamber bags. Certain cases might require individually prepared solutions, for example if patients suffer from a high loss of volume and electrolytes. In addition to multi-chamber bags, there are also total nutrition solutions (GSL) with pre-prepared mixtures.

Calculating the quantity

What and how much a patient needs depends on various factors:

- current body weight

- current laboratory values

- with or without oral/enteral nutritional supplements

- severe volume loss (e.g. due to vomiting/stomata)

With a stable metabolism, the daily energy requirement ranges between 25 to 35 kcal per kg body weight. For overweight patients on parenteral nutrition, the recommended normal weight (BMI of 25) serves as the calculating reference, whereby the protein intake should amount to at least 1.5 g/kg. For normal and underweight patients, the current weight serves as reference. Regular controls must ensure that the calculated amount is sufficient. If necessary, adjustments are made to achieve a certain weight or to maintain the general state of health.

Apart from the quantity, the speed of food intake also plays an important role. The maximum values are:

- 0.25 g glucose per hour & kg body weight

- 0.125 g fat per hour & kg body weight

Exceeded values can massively impair the metabolism. However, it is quite possible (and often sensible) to slow down the infusion. Especially in the beginning, patients should start with half the speed and quantity and then gradually increase it over the course of two to three days. An infusion pump helps to provide an even intake of all nutrient components.

Reference quantities for parenteral nutrition

| Per kg/day | |

| Energy requirement (total = parenteral/enteral/oral) |

25-35 kcal |

| Glucose | 2-3.5 g (max. 4 g) |

| Fat | 0.7-1.5 g (max. 2 g) |

| Amino acids | 0.8-1.5 g |

| Liquids | 35-40 ml (possibly more in case of increased loss/shortage) |

Parenteral nutrient solutions can only be absorbed directly through a vein due to their high concentration (compared to human blood). There are several options for this. The choice of access route depends on the expected duration of intravenous nutrition.

Central-venous access (i.e. access through a large body vein, e.g. superior vena cava) is normally used for parenteral nutrition. Peripheral access via smaller veins comes with a higher risk of inflammation or blood clots.

| Access | Features | Use for parenteral nutrition |

| Central-venous catheter (CVC) |

|

|

| Port |

|

|

| Subcutaneously tunneled catheter |

|

|

Intravenous nutrition can take place both in inpatient settings and at home. In hospitals, clinics, and care facilities, staff take care of the entire process. Apart from the infusions, this includes tasks such as dressing changes and weight checks. Patients with a stable metabolism (and permanent central-venous access) can largely do all of this themselves. This is called home parenteral nutrition (HPE). Patients (and their relatives) must be trained in advance and supported by medical professionals. This is usually done by outpatient care services or homecare companies.

- Nursing services provide basic medical care and treatment. This also includes specialized outpatient palliative care.

- Homecare companies offer additional services, such as support in organisational and bureaucratic matters.

The intensity of care depends on the patient's state of health. Patients with a stable metabolism can postpone most of their food intake to the night. The infusion normally runs for 16 to 18 hours a day, although the times vary according to the patient's tolerance. During the day, patients can pursue professional activities and participate in social life. If necessary, it is also possible to administer parenteral nutrition outside the home. Patients then carry the infusion bag (and other accessories) in a backpack with them. However, experts generally recommend administering the infusion at home in familiar surroundings. This is the safest way to make sure that the required hygiene standards are maintained.

Regular checks are essential in both inpatient and home settings. The most important indicator is the number on the scale: The patient’s weight indicates whether the composition of the nutrient solutions can stay the same or may need adjustments. Moreover, the medical team must also take the patient’s subjective perception into account:

- How do they feel during infusions and in-between?

- Do they experience any unexpected or unpleasant side effects?

In principle, the infusion should only administer as much food as can be metabolized. When laboratory values indicate that certain limit values are exceeded, the quantity must be reduced – even if this means that the administered quantity falls below the calculated energy or nutrient requirement. Regular monitoring (at least once a week) is particularly important at the beginning of intravenous nutrition. As long as no abnormalities are observed and the metabolism remains stable, the interval between checks can be increased to up to three months.

Laboratory values as parameters for parenteral nutrition

- electrolytes (sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, phosphate)

- glucose

- triglycerides (marker for sugar and fat metabolism)

- protein (especially C-reactive protein (CRP) as a marker for inflammation)

- albumin (may indicate liver diseases or disorders of the water balance)

- creatinine (marker for kidney function)

- urea (possible indicator for kidney disease)

- transaminases (may indicate liver or heart disease)

- bilirubin (may indicate breakdown of red blood cells)

Limit values for parenteral nutrition

|

Value |

Limit | Measure in case of overrun |

|

Glucose (with infusion running) |

min. 180 mg/dl | reduce glucose intake |

| Triglycerides (with infusion running) |

max. 400 mg/dl | reduce fat intake |

| Urea | increase by 30 mg/dl | reduce amino acid intake (does not apply in case of renal insufficiency) |

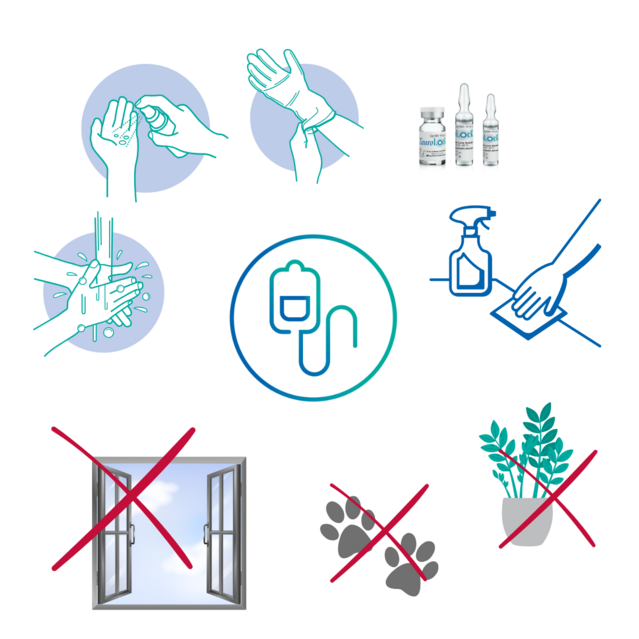

Hygiene measures for home parenteral nutrition

To ensure a smooth process, the nutrient solution and access must remain absolutely sterile at all times. Therefore, patients and staff must maintain the highest hygiene standards. This is especially important for patients on home parenteral nutrition, as they come into contact with germs even more quickly than in at inpatient facilities.

- Dressing changes and infusions may only be carried out by trained persons. This can be a nurse, or patients and relatives.

- The preparation and application of the nutrient solutions should always take place in a fixed location. The respective room should not contain any plants and not be accessible to pets.

- Doors and windows should remain closed while patients handle catheters and bags. Draughts can allow germs to enter and spread in a room more quickly.

- The outer end of the catheter and the puncture site must not become wet. Patients should therefore wear a water-repellent film dressing when they shower or wash themselves.

PN patients are exposed to a variety of risks. Metabolic complications (i.e. metabolic disorders) can occur if the nutrient solution does not fully meet individual needs. Mechanical complications, i.e. problems with the access system, might also occur.

These risks can largely be avoided with careful monitoring and proper handling of the catheter. However, the greatest risk is microbial colonisation of the catheter. This means that microorganisms such as viruses, bacteria or fungi multiply on or in the access. These microorganisms can enter the bloodstream and cause a catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI). Such an infection can show itself early on through various symptoms. In particular, classic signs of inflammation serve as warning signals:

- redness or swelling around the catheter

- heightened sensitivity to pain

- overheating (fever, chills)

- poorer flow rate

- headache, nausea, vomiting

If such symptoms become noticeable, patients should seek medical advice immediately. In the worst case, CRBSI can be fatal. But even if the danger is not as severe, these infections can significantly impair a patient’s quality of life – especially when they occur repeatedly and require hospitalisation. Prevention thus remains the end-all, be-all in parenteral nutrition.

| Metabolic complications | Mechanical complications |

|

|

Protection with lock solutions

Strict hygiene standards alone are not enough to prevent infections. The catheter must also be rinsed with a physiological saline solution after each session. We recommend the pulsatile flushing technique with 2x10 ml ready-to-use saline syringes.[2]

In addition, the catheter must be locked with a special solution.

- The lock solution is injected into the catheter after the end of an infusion and remains there until the next one.

- This prevents blood from entering the catheter and germs from colonising it. (Germs that enter the organism from outside present a particularly dangerous threat.)

For effective protection against microorganisms, a lock solution must have active ingredients with antimicrobial properties. Taurolidine has proven particularly effective in that regard. It is a synthetically produced derivative of the amino acid taurine. (Taurine occurs naturally in the human body and can often be found in energy drinks).

- Taurolidine stands out with a broad effectiveness against more than 500 different bacteria and fungi – whereas antibiotics are only effective against certain types of germs.

- Moreover, taurolidine does not lead to the development of bacterial resistance – a common side effect of antibiotics that erases antibacterial effectiveness.

For these reasons, taurolidine constitutes the basis for all products of the portfolio developed by TauroPharm. Depending on the patient’s requirements, there are different product variants available. Some of these variants also contain other active ingredients. The additional active ingredients primarily serve to maintain the patency of the catheter.

Lock solutions for parenteral nutrition

|

Product |

Active ingredients | Application |

|---|---|---|

|

|

all patients without specific abnormalities |

|

|

patients at risk of insufficient patency |

|

|

extra strong prophylaxis against occlusion and thrombosis |

|

|

patients with poor citrate tolerance (especially young children) |

Numerous clinical studies have examined taurolidine-based lock solutions in parenteral nutrition.

- A 2017 study investigated the use of TauroLock™-HEP100 in HPN. Among the 20 patients who used the product regularly over several years, not a single CRBSI occurred.[3]

- One year later, a study on the efficacy of TauroLock™ in children with HPN was published. Among the 40 children who received TauroLock™, the CRBSI rate decreased from 4.16 to 0.25 (per 1,000 catheter days) over a 6-year period.[4]

- In 2020, a long-term study was published that had run for 19 years. Among patients using TauroLock™-HEP100, the rate of catheter infections decreased from 2.36 to 0.3 (per 1,000 catheter days).[5]

Based on these findings, experts now recommend taurolidine in national and international guidelines for parenteral nutrition.

- According to the German Society for Nutritional Medicine (DGEM), taurolidine-containing lock solutions should be used in patients at high and normal risk of CRBSI. [6]

- The guideline of the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) recommends the use of taurolidine for the prevention of CRBSI. [7]

Dependence on intravenous nutrition often presents patients with bureaucratic challenges. Generally speaking, health insurance covers the costs of nutrient solutions and some aids (e.g. cannulas, pumps or syringes). However, not all of the aids required are covered by insurance. Patients might have to pay for accessories such as disinfectants, sterile wipes, or infusion stands.

In Germany, training for home parenteral nutrition and the use of nursing services is usually covered by health insurance. This does not necessarily require a care degree classification. Those with public health insurance just need to submit a certificate of necessity from the doctor treating them. For people with private insurance, the benefits depend on the individual tariff.

- https://www.g-ba.de/downloads/92-975-1638/2016-08-01_Bewertung-Therapiekosten-Patientenzahlen-IQWiG_Teduglutid-nAWG_D-254.pdf

- Goossens. Dialysis & Apharesis 2015.

- Tribler et al. Am J Clin Nutr 2017. DOI: 10.3945/ajcn.117.158964

- Lambe et al. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2018. DOI: 10.1002/jpen.1043

- Leiberman et al. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2020 DOI: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2020.03.025

- Bischoff et al. Aktuell Ernahrungsmed 2024. DOI: 10.1055/a-2270-7667

- Pironi et al. Clin Nutr 2020 DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.03.005